“Will AI Destroy Us?”: Roundtable with Coleman Hughes, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Gary Marcus, and me (+ GPT-4-enabled transcript!)

Saturday, July 29th, 2023A month ago Coleman Hughes, a young writer whose name I recognized from his many thoughtful essays in Quillette and elsewhere, set up a virtual “AI safety roundtable” with Eliezer Yudkowsky, Gary Marcus, and, err, yours truly, for his Conversations with Coleman podcast series. Maybe Coleman was looking for three people with the most widely divergent worldviews who still accept the premise that AI could, indeed, go catastrophically for the human race, and that talking about that is not merely a “distraction” from near-term harms. In any case, the result was that you sometimes got me and Gary against Eliezer, sometimes me and Eliezer against Gary, and occasionally even Eliezer and Gary against me … so I think it went well!

You can watch the roundtable here on YouTube, or listen here on Apple Podcasts. (My one quibble with Coleman’s intro: extremely fortunately for both me and my colleagues, I’m not the chair of the CS department at UT Austin; that would be Don Fussell. I’m merely the “Schlumberger Chair,” which has no leadership responsibilities.)

I know many of my readers are old fuddy-duddies like me who prefer reading to watching or listening. Fortunately, and appropriately for the subject matter, I’ve recently come into possession of a Python script that grabs the automatically-generated subtitles from any desired YouTube video, and then uses GPT-4 to edit those subtitles into a coherent-looking transcript. It wasn’t perfect—I had to edit the results further to produce what you see below—but it was still a huge time savings for me compared to starting with the raw subtitles. I expect that in a year or two, if not sooner, we’ll have AIs that can do better still by directly processing the original audio (which would tell the AIs who’s speaking when, the intonations of their voices, etc).

Anyway, thanks so much to Coleman, Eliezer, and Gary for a stimulating conversation, and to everyone else, enjoy (if that’s the right word)!

PS. As a free bonus, here’s a GPT-4-assisted transcript of my recent podcast with James Knight, about common knowledge and Aumann’s agreement theorem. I prepared this transcript for my fellow textophile Steven Pinker and am now sharing it with the world!

PPS. I’ve now added links to the transcript and fixed errors. And I’ve been grateful, as always, for the reactions on Twitter (oops, I mean “X”), such as: “Skipping all the bits where Aaronson talks made this almost bearable to watch.”

COLEMAN: Why is AI going to destroy us? ChatGPT seems pretty nice. I use it every day. What’s, uh, what’s the big fear here? Make the case.

ELIEZER: We don’t understand the things that we build. The AIs are grown more than built, you might say. They end up as giant inscrutable matrices of floating point numbers that nobody can decode. At this rate, we end up with something that is smarter than us, smarter than humanity, that we don’t understand. Whose preferences we could not shape and by default, if that happens, if you have something around it, it is like much smarter than you and does not care about you one way or the other. You probably end up dead at the end of that.

GARY: Extinction is a pretty, you know, extreme outcome that I don’t think is particularly likely. But the possibility that these machines will cause mayhem because we don’t know how to enforce that they do what we want them to do, I think that’s a real thing to worry about.

[Music]

COLEMAN: Welcome to another episode of Conversations with Coleman. Today’s episode is a roundtable discussion about AI safety with Eliezer Yudkowsky, Gary Marcus, and Scott Aaronson.

Eliezer Yudkowsky is a prominent AI researcher and writer known for co-founding the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, where he spearheaded research on AI safety. He’s also widely recognized for his influential writings on the topic of rationality.

Scott Aaronson is a theoretical computer scientist and author, celebrated for his pioneering work in the field of quantum computation. He’s also the [Schlumberger] Chair of CompSci at U of T Austin, but is currently taking a leave of absence to work at OpenAI.

Gary Marcus is a cognitive scientist, author, and entrepreneur known for his work at the intersection of psychology, linguistics, and AI. He’s also authored several books including Kluge and Rebooting AI: Building AI We Can Trust.

This episode is all about AI safety. We talk about the alignment problem, we talk about the possibility of human extinction due to AI. We talk about what intelligence actually is, we talk about the notion of a singularity or an AI takeoff event, and much more. It was really great to get these three guys in the same virtual room, and I think you’ll find that this conversation brings something a bit fresh to a topic that has admittedly been beaten to death on certain corners of the internet.

So, without further ado, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Gary Marcus, and Scott Aaronson. [Music]

Okay, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Scott Aaronson, Gary Marcus, thanks so much for coming on my show. Thank you. So, the topic of today’s conversation is AI safety and this is something that’s been in the news lately. We’ve seen, you know, experts and CEOs signing letters recommending public policy surrounding regulation. We continue to have the debate between people that really fear AI is going to end the world and potentially kill all of humanity and the people who fear that those fears are overblown. And so, this is going to be sort of a roundtable conversation about that, and you three are really three of the best people in the world to talk about it with. So thank you all for doing this.

Let’s just start out with you, Eliezer, because you’ve been one of the most really influential voices getting people to take seriously the possibility that AI will kill us all. You know, why is AI going to destroy us? ChatGPT seems pretty nice. I use it every day. What’s the big fear here? Make the case.

ELIEZER: Well, ChatGPT seems quite unlikely to kill everyone in its present state. AI capabilities keep on advancing and advancing. The question is not, “Can ChatGPT kill us?” The answer is probably no. So as long as that’s true, as long as it hasn’t killed us yet, the engineers are just gonna keep pushing the capabilities. There’s no obvious blocking point.

We don’t understand the things that we build. The AIs are grown more than built, you might say. They end up as giant inscrutable matrices of floating point numbers that nobody can decode. It’s probably going to end up technically difficult to make them want particular things and not others, and people are just charging straight ahead. So, at this rate, we end up with something that is smarter than us, smarter than humanity, that we don’t understand, whose preferences we could not shape.

By default, if that happens, if you have something around that is much smarter than you and does not care about you one way or the other, you probably end up dead. At the end of that, it gets the most of whatever strange and inscrutable things that it wants: it wants worlds in which there are not humans taking up space, using up resources, building other AIs to compete with it, or it just wants a world in which you built enough power plants that the surface of the earth gets hot enough that humans didn’t survive.

COLEMAN: Gary, what do you have to say about that?

GARY: There are parts that I agree with, some parts that I don’t. I agree that we are likely to wind up with AIs that are smarter than us. I don’t think we’re particularly close now, but you know, in 10 years or 50 years or 100 years, at some point, it could be a thousand years, but it will happen.

I think there’s a lot of anthropomorphization there about the machines wanting things. Of course, they have objective functions, and we can talk about that. I think it’s a presumption to say that the default is that they’re going to want something that leads to our demise, and that they’re going to be effective at that and be able to literally kill us all.

I think, if you look at the history of AI, at least so far, they don’t really have wants beyond what we program them to do. There is an alignment problem, I think that that’s real in the sense of like people who program the system to do X and they do X’, that’s kind of like X but not exactly. And so, I think there’s really things to worry about. I think there’s a real research program here that is under-researched.

But the way I would put it is, we want to understand how to make machines that have values. You know Asimov’s laws are way too simple, but they’re a kind of starting point for conversation. We want to program machines that don’t harm humans. They can calculate the consequences of their actions. Right now, we have technology like GPT-4 that has no idea what the consequence of its actions are; it doesn’t really anticipate things.

And there’s a separate thing that Eliezer didn’t emphasize, which is, it’s not just how smart the machines are but how much power we give them; how much we empower them to do things like access the internet or manipulate people, or, um, you know, write source code, access files and stuff like that. Right now, AutoGPT can do all of those things, and that’s actually pretty disconcerting to me. To me, that doesn’t all add up to any kind of extinction risk anytime soon, but catastrophic risk where things go pretty wrong because we wanted these systems to do X and we didn’t really specify it well. They don’t really understand our intentions. I think there are risks like that.

I don’t see it as a default that we wind up with extinction. I think it’s pretty hard to actually terminate the entire human species. You’re going to have people in Antarctica; they’re going to be out of harm’s way or whatever, or you’re going to have some people who, you know, respond differently to any pathogen, etc. So, like, extinction is a pretty extreme outcome that I don’t think is particularly likely. But the possibility that these machines will cause mayhem because we don’t know how to enforce that they do what we want them to do – I think that’s a real thing to worry about and it’s certainly worth doing research on.

COLEMAN: Scott, how do you view this?

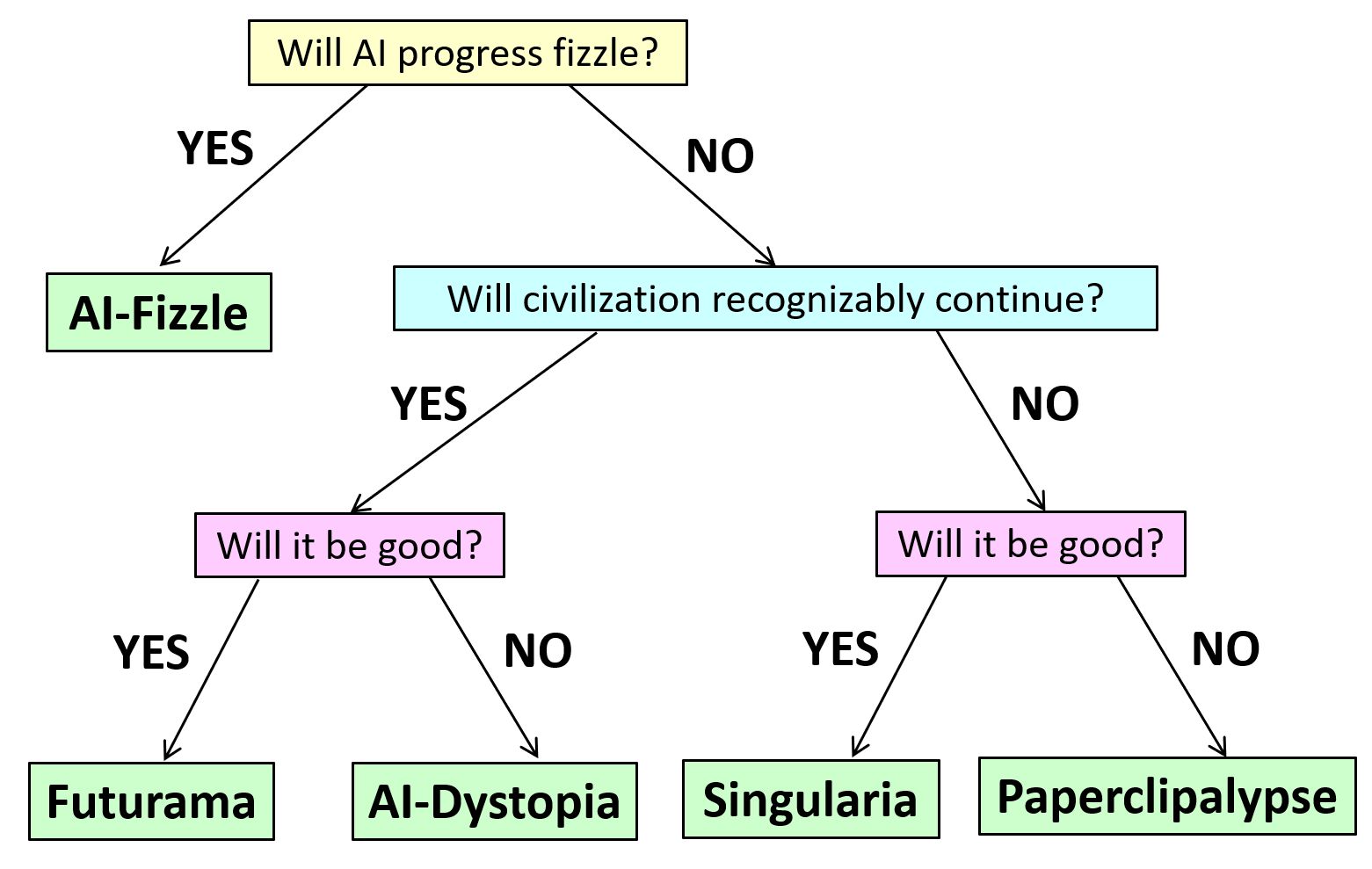

SCOTT: So I’m sure that you can get the three of us arguing about something, but I think you’re going to get agreement from all three of us that AI safety is important. That catastrophic outcomes, whether or not they mean literal human extinction, are possible. I think it’s become apparent over the last few years that this century is going to be largely defined by our interaction with AI. That AI is going to be transformative for human civilization and—I’m confident about that much. If you ask me almost anything beyond that about how it’s going to transform civilization, will it be good, will it be bad, what will the AI want, I am pretty agnostic. Just because, if you would have asked me 20 years ago to try to forecast where we are now, I would have gotten a lot wrong.

My only defense is that I think all of us here and almost everyone in the world would have gotten a lot wrong about where we are now. If I try to envision where we are in 2043, does the AI want to replace humanity with something better, does it want to keep us around as pets, does it want to continue helping us out, like a super souped-up version of ChatGPT, I think all of those scenarios merit consideration.

What has happened in the last few years that’s really exciting is that AI safety has become an empirical subject. Right now, there are very powerful AIs that are being deployed and we can actually learn something. We can work on mitigating the nearer-term harms. Not because the existential risk doesn’t exist, or is absurd or is science fiction or anything like that, but just because the nearer-term harms are the ones that we can see right in front of us. And where we can actually get feedback from the external world about how we’re doing. We can learn something and hopefully some of the knowledge that we gain will be useful in addressing the longer term risks, that I think Eliezer is very rightly worried about.

COLEMAN: So, there’s alignment and then there’s alignment, right? So there’s alignment in the sense that we haven’t even fully aligned smartphone technology with our interests. Like, there are some ways in which smartphones and social media have led to probably deleterious mental health outcomes, especially for teenage girls for example. So there are those kinds of mundane senses of alignment where it’s like, ‘Is this technology doing more good than harm in the normal everyday public policy sense?’ And then there’s the capital ‘A’ alignment. Are we creating a creature that is going to view us like ants and have no problem extinguishing us, whether intentional or not?

So it seems to me all of you agree that the first sense of alignment is, at the very least, something to worry about now and something to deal with. But I’m curious to what extent you think the really capital ‘A’ sense of alignment is a real problem because it can sound very much like science fiction to people. So maybe let’s start with Eliezer.

ELIEZER: I mean, from my perspective, I would say that if we had a solid guarantee that AI was going to do no more harm than social media, we ought to plow ahead and reap all the gains. The amount of harm that social media has done to humanity, while significant in my view and having done a lot of damage to our sanity, is not enough harm to justify either foregoing the gains that you could get from AI— if that was going to be the worst downside—or to justify the kind of drastic measures you’d need to stop plowing ahead on AI.

I think that the capital “A” alignment is beyond this generation. Yeah, you know, I’ve started in the field, I’ve watched over it for two decades. I feel like in some ways, the modern generation, plowing in with their eyes on the short-term stuff, is losing track of the larger problems because they can’t solve the larger problems, and they can solve the little problems. But we’re just plowing straight into the big problems, and we’re going to plow right into the big problems with a bunch of little solutions that aren’t going to scale.

I think it’s cool. I think it’s lethal. I think it’s at the scale where you just back off and don’t do this.

COLEMAN: By “back off and don’t do this,” what do you mean?

ELIEZER: I mean, have an international treaty about where the chips capable of doing AI training go, and have them all going into licensed, monitored data centers. And not have the training runs for AI’s more powerful than GPT-4, possibly even lowering that threshold over time as algorithms improve, and it gets power possible to train more powerful AIs using lessons—

COLEMAN: So you’re picturing a kind of international agreement to just stop? International moratorium?

ELIEZER: If North Korea steals the GPU shipment, then you’ve got to be ready to destroy their data center that they build by conventional means. And if you don’t have that willingness in advance, then countries may refuse to sign up for the agreement being, like, ‘Why aren’t we just ceding the advantage to someone else?’

Then, it actually has to be a worldwide shutdown because the scale of harmfulness super intelligence—it’s not that if you have 10 times as many super intelligences, you’ve got 10 times as much harm. It’s not that a superintelligence only wrecks the country that built the superintelligence. Any superintelligence anywhere is everyone’s last problem.

COLEMAN: So, Gary and Scott, if either of you want to jump in there, I mean, is there—is AI safety a matter of forestalling the end of the world? And all of these smaller issues and paths towards safety that Scott, you mentioned, are they—just, you know—throwing I don’t know what the analogy is but um, pointless essentially? I mean, what do you guys make of this?

SCOTT: The journey of a thousand miles begins with a step, right? Most of the way I think about this comes from, you know, 25 years of doing computer science research, including quantum computing and computational complexity, things like that. We have these gigantic aspirational problems that we don’t know how to solve and yet, year after year, we do make progress. We pick off little sub-problems, and if we can’t solve those, then we find sub-problems of those. And we keep repeating until we find something that we can solve. And this is, I think, for centuries, the way that science has made progress. Now it is possible, of course, that this time, we just don’t have enough time for that to work.

And I think that is what Eliezer is fearful of, right? That we just don’t have enough time for the ordinary scientific process to take place before AI becomes too powerful. In such a case, you start talking about things like a global moratorium, enforced with the threat of war.

However, I am not ready to go there. I could imagine circumstances where I might say, ‘Gosh, this looks like such an imminent threat that, you know, we have to intervene.’ But, I tend to be very worried in general about causing a catastrophe in the process of trying to prevent one. And I think, when you’re talking about threatening airstrikes against data centers or similar actions, then that’s an obvious worry.

GARY: I’m somewhat in between here. I agree with Scott that we are not at the point where we should be bombing data centers. I don’t think we’re close to that. Furthermore, I’m much less optimistic about our proximity to AGI than Eliezer sometimes sounds like. I don’t think GPT-5 is anything like AGI, and I’m not particularly concerned about who gets it first and so forth. On the other hand, I think that we’re in a sort of dress rehearsal mode.

You know, nobody expected GPT-4, or really ChatGPT, to percolate as fast as it did. And it’s a reminder that there’s a social side to all of this. How software gets distributed matters, and there’s a corporate side as well.

It was a kind of galvanizing moment for me when Microsoft didn’t pull Sydney, even though Sydney did some awfully strange things. I thought they would stop it for a while and it’s a reminder that they can make whatever decisions they want. So, when we multiply that by Eliezer’s concerns about what do we do and at what point would it be enough to cause problems, it is a reminder I think, that we need, for example, to start drafting these international treaties now because there could become a moment where there is a problem.

I don’t think the problem that Eliezer sees is here now, but maybe it will be. And maybe when it does come, we will have so many people pursuing commercial self-interest and so little infrastructure in place, we won’t be able to do anything. So, I think it really is important to think now—if we reach such a point, what are we going to do? And what do we need to build in place before we get to that point.

COLEMAN: We’ve been talking about this concept of Artificial General Intelligence and I think it’s worth asking whether that is a useful, coherent concept. So for example, if I were to think of my analogy to athleticism and think of the moment when we build a machine that has, say, artificial general athleticism meaning it’s better than LeBron James at basketball, but also better at curling than the world’s best curling player, and also better at soccer, and also better at archery and so forth. It would seem to me that there’s something a bit strange in framing it as having reached a point on a single continuum. It seems to me you would sort of have to build each capability, each sport individually, and then somehow figure how to package them all into one robot without each skill set detracting from the other.

Is that a disanalogy? Is there a different way you all picture this intelligence as sort of one dimension, one knob that is going to get turned up along a single axis? Or do you think that way of talking about it is misleading in the same way that I kind of just sketched out?

GARY: Yeah, I would absolutely not accept that. I’d like to say that intelligence is not a one-dimensional variable. There are many different aspects to intelligence and I don’t think there’s going to be a magical moment when we reach the singularity or something like that.

I would say that the core of artificial general intelligence is the ability to flexibly deal with new problems that you haven’t seen before. The current systems can do that a little bit, but not very well. My typical example of this now is GPT-4. It is exposed to the game of chess, sees lots of games of chess, sees the rules of chess but it never actually figure out the rules of chess. They often make illegal moves and so forth. So it’s in no way a general intelligence that can just pick up new things. Of course, we have things like AlphaGo that can play a certain set of games or AlphaZero really, but we don’t have anything that has the generality of human intelligence.

However, human intelligence is just one example of general intelligence. You could argue that chimpanzees or crows have another variety of general intelligence. I would say that current machines don’t really have it but they will eventually.

SCOTT: I think a priori, it could have been that you would have math ability, you would have verbal ability, you’d have the ability to understand humor, and they’d all be just completely unrelated to each other. That is possible and in fact, already with GPT, you can say that in some ways it’s already a superintelligence. It knows vastly more, can converse on a vastly greater range of subjects than any human can. And in other ways, it seems to fall short of what humans know or can do.

But you also see this sort of generality just empirically. I mean, GPT was trained on most of the text on the open internet. So it was just one method. It was not explicitly designed to write code, and yet, it can write code. And at the same time as that ability emerged, you also saw the ability to solve word problems, like high school level math. You saw the ability to write poetry. This all came out of the same system without any of it being explicitly optimized for.

GARY: I feel like I need to interject one important thing, which is – it can do all these things, but none of them all that reliably well.

SCOTT: Okay, nevertheless, I mean compared to what, let’s say, my expectations would have been if you’d asked me 10 or 20 years ago, I think that the level of generality is pretty remarkable. It does lend support to the idea that there is some sort of general quality of understanding there. For example, you could say that GPT-4 has more of it than GPT-3, which in turn has more than GPT-2.

ELIEZER: It does seem to me like it’s presently pretty unambiguous that GPT-4 is, in some sense, dumber than an adult or even a teenage human. And…

COLEMAN: That’s not obvious to me.

GARY: I mean, to take the example I just gave you a minute ago, it never learns to play chess even with a huge amount of data. It will play a little bit of chess; it will memorize the openings and be okay for the first 15 moves. But, it gets far enough away from what it’s trained on, and it falls apart. This is characteristic of these systems. It’s not really characteristic in the same way of adults or even teenage humans. Almost, I feel that it does, it does unreliably. Let me give another example. You can ask a human to write a biography of someone and not make stuff up, and you really can’t ask GPT to do that.

ELIEZER: Yeah, like it’s a bit difficult because you could always be cherry-picking something that humans are unusually good at. But to me, it does seem like there’s this broad range of problems that don’t seem especially to play to humans’ strong points or machine weak points. For where GPT-4 will, you know, do no better than a seven-year-old on those problems.

COLEMAN: I do feel like these examples are cherry-picked. Because if I, if I just take a different, very typical example – I’m writing an op-ed for the New York Times, say about any given subject in the world, and my choice is to have a smart 14-year-old next to me with anything that’s in his mind already or GPT – there’s no comparison, right? So, which of these examples is the litmus test for who’s more intelligent, right?

GARY: If you did it on a topic where it couldn’t rely on memorized text, you might actually change your mind on that. So I mean, the thing about writing a Times op-ed is, most of the things that you propose to it, there’s actually something that it can pastiche together from its dataset. But, that doesn’t mean that it really understands what’s going on. It doesn’t mean that that’s a general capability.

ELIEZER: Also, as the human, you’re doing all the hard parts. Right, like obviously, a human is going to prefer – if a human has a math problem, he’s going to rather use a calculator than another human. And similarly, with the New York Times op-ed, you’re doing all the parts that are hard for GPT-4, and then you’re asking GPT-4 to just do some of the parts that are hard for you. You’re always going to prefer an AI partner rather than a human partner, you know, within that sort of range. The human can do all the human stuff and you want an AI to do whatever the AI is good at the moment, right?

GARY: A relevant analogy here is driverless cars. It turns out, on highways and ordinary traffic, they’re probably better than people. But in unusual circumstances, they’re really worse than people. For instance, a Tesla not too long ago ran into a jet at slow speed while being summoned across a parking lot. A human wouldn’t have done that, so there are different strengths and weaknesses.

The strength of a lot of the current kinds of technology is that they can either patch things together or make non-literal analogies; we’ll go into details, but they can pull from stored examples. They tend to be poor when you get to outlier cases, and this is persistent across most of the technologies that we use right now. Therefore, if you stick to stuff for which there’s a lot of data, you’ll be happy with the results you get from these systems. But if you move far enough away, not so much.

ELIEZER: What we’re going to see over time is that the debate about whether or not it’s still dumber than you will continue for longer and longer. Then, if things are allowed to just keep running and nobody dies, at some point, it switches over to a very long debate about ‘is it smarter than you?’ which then gets shorter and shorter and shorter. Eventually it reaches a point where it’s pretty unambiguous if you’re paying attention. Now, I suspect that this process gets interrupted by everybody dying. In particular, there’s a question of the point at which it becomes better than you, better than humanity at building the next edition of the AI system. And how fast do things snowball once you get to that point? Possibly, you do not have time for further public debates or even a two-hour Twitter space depending on how that goes.

SCOTT: I mean, some of the limitations of GPT are completely understandable, just from a little knowledge of how it works. For example, it doesn’t have an internal memory per se, other than what appears on the screen in front of you. This is why it’s turned out to be so effective to explicitly tell it to think step-by-step when it’s solving a math problem. You have to tell it to show all of its work because it doesn’t have an internal memory with which to do that.

Likewise, when people complain about it hallucinating references that don’t exist, well, the truth is when someone asks me for a citation and I’m not allowed to use Google, I might have a vague recollection of some of the authors, and I’ll probably do a very similar thing to what GPT does: I’ll hallucinate.

GARY: So there’s a great phrase I learned the other day, which is ‘frequently wrong, never in doubt.’

SCOTT: That’s true, that’s true.

GARY: I’m not going to make up a reference with full detail, page numbers, titles, and so forth. I might say, ‘Look, I don’t remember, you know, 2012 or something like that.’ Yeah, whereas GPT-4, what it’s going to say is, ‘2017, Aaronson and Yudkowsky, you know, New York Times, pages 13 to 17.’

SCOTT: No, it does need to get much much better at knowing what it doesn’t know. And yet already I’ve seen a noticeable improvement there, going from GPT-3 to GPT-4.

For example, if you ask GPT-3, ‘Prove that there are only finitely many prime numbers,’ it will give you a proof, even though the statement is false. It will have an error which is similar to the errors on a thousand exams that I’ve graded, trying to get something past you, hoping that you won’t notice. Okay, if you ask GPT-4, ‘Prove that there are only finitely many prime numbers,’ it says, ‘No, that’s a trick question. Actually, there are infinitely many primes and here’s why.’

GARY: Yeah, part of the problem with doing the science here is that — I think, you would know better since you work part-time, or whatever, at OpenAI — but my sense is that a lot of the examples that get posted on Twitter, particularly by the likes of me and other critics, or other skeptics I should say, is that the system gets trained on those. Almost everything that people write about it, I think, is in the training set. So it’s hard to do the science when the system’s constantly being trained, especially in the RLHF side of things. And we don’t actually know what’s in GPT-4, so we don’t even know if there are regular expressions and, you know, simple rules or such things. So we can’t do the kind of science we used to be able to do.

ELIEZER: This conversation, this subtree of the conversation, I think, has no natural endpoint. So, if I can sort of zoom out a bit, I think there’s a pretty solid sense in which humans are more generally intelligent than chimpanzees. As you get closer and closer to the human level, I would say that the direction here is still clear. The comparison is still clear. We are still smarter than GPT-4. This is not going to take control of the world from us.

But, you know, the conversations get longer, the definitions start to break down around the edges. But I think it also, as you keep going, it comes back together again. There’s a point, and possibly this point is very close to the point of time to where everybody dies, so maybe we don’t ever see it in a podcast. But there’s a point where it’s unambiguously smarter than you, including like the spark of creativity, being able to deduce things quickly rather than with tons and tons of extra evidence, strategy, cunning, modeling people, figuring out how to manipulate people.

GARY: So, let’s stipulate, Eliezer, that we’re going to get to machines that can do all of that. And then the question is, what are they going to do? Is it a certainty that they will make our annihilation part of their business? Is it a possibility? Is it an unlikely possibility?

I think your view is that it’s a certainty. I’ve never really understood that part.

ELIEZER: It’s a certainty on the present tech, is the way I would put it. Like, if that happened tomorrow, then you know, modulo Cromwell’s Rule, never say certain. My probability is like yes, modulo like the chance that my model is somehow just completely mistaken.

If we got 50 years to work it out and unlimited retries, I’d be a lot more confident. I think that’d be pretty okay. I think we’d make it. The problem is that it’s a lot harder to do science when your first wrong attempt destroys the human species and then you don’t get to try again.

GARY: I mean, I think there’s something again that I agree with and something I’m a little bit skeptical about. So I agree that the amount of time we have matters. And I would also agree that there’s no existing technology that solves the alignment problem, that gives a moral basis to these machines.

I mean, GPT-4 is fundamentally amoral. I don’t think it’s immoral. It’s not out to get us, but it really is amoral. It can answer trolley problems because there are trolley problems in the dataset, but that doesn’t mean that it really has a moral understanding of the world.

And so if we get to a very smart machine that, by all the criteria that we’ve talked about, is amoral, then that’s a problem for us. There’s a question of whether, if we can get to smart machines, whether we can build them in a way that will have some moral basis…

ELIEZER: On the first try?

GARY: Well, the first try part I’m not willing to let pass. So, I understand, I think your argument there; maybe you should spell it out. I think that we’ll probably get more than one shot, and that it’s not as dramatic and instantaneous as you think. I do think one wants to think about sandboxing and wants to think about distribution.

But let’s say we had one evil super-genius now who is smarter than everybody else. Like, so what? One super-

ELIEZER: Much smarter? Not just a little smarter?

GARY: Oh, even a lot smarter. Like most super-geniuses, you know, aren’t actually that effective. They’re not that focused; they’re focused on other things. You’re kind of assuming that the first super-genius AI is gonna make it its business to annihilate us, and that’s the part where I’m still a bit stuck in the argument.

ELIEZER: Yeah, some of this has to do with the notion that if you do a bunch of training you start to get goal direction, even if you don’t explicitly train on that. That goal direction is a natural way to achieve higher capabilities. The reason why humans want things is that wanting things is an effective way of getting things. And so, natural selection in the process of selecting exclusively on reproductive fitness, just on that one thing, got us to want a bunch of things that correlated with reproductive fitness in the ancestral distribution because wanting, having intelligences that want things, is a good way of getting things. That’s, in a sense, like, wanting comes from the same place as intelligence itself. And you could even, from a certain technical standpoint on expected utilities, say that intelligence is a special, is a very effective way of wanting – planning, plotting paths through time that leads to particular outcomes.

So, part of it is that I think it, I do not think you get like the brooding super-intelligence that wants nothing because I don’t think that wanting and intelligence can be pried apart that easily. I think that the way you get super-intelligence is that there are things that have gotten good at organizing their own thoughts and have good taste in which thoughts to think. And that is where the high capabilities come from.

COLEMAN: Let me just put the following point to you, which I think, in my mind, is similar to what Gary was saying. There’s often, in philosophy, this notion of the Continuum Fallacy. The canonical example is like you can’t locate a single hair that you would pluck from my head where I would suddenly go from not bald to bald. Or, like, the even more intuitive examples, like a color wheel. Like there’s no single pixel on a grayscale you can point to and say, well that’s where gray begins and white ends. And yet, we have this conceptual distinction that feels hard and fast between gray and white, and gray and black, and so forth.

When we’re talking about artificial general intelligence or superintelligence, you seem to operate on a model where either it’s a superintelligence capable of destroying all of us or it’s not. Whereas, intelligence may just be a continuum fallacy-style spectrum, where we’re first going to see the shades of something that’s just a bit more intelligent than us, and maybe it can kill five people at most. And when that happens, you know, we’re going to want to intervene, and we’re going to figure out how to intervene and so on and so forth.

ELIEZER: Yeah, so if it’s stupid enough to do it then yes. Let me assure you, by employing the identical logic, there should be nobody who steals money on a really large scale, right? Because you could just give them five dollars and see if they steal that, and if they don’t steal that, you know, you’re good to trust them with a billion.

SCOTT: I think that in actuality, anyone who did steal a billion dollars probably displayed some dishonest behavior earlier in their life which was, unfortunately, not acted upon early enough.

COLEMAN: The analogy is like, we have the first case of fraud that’s ten thousand dollars, and then we build systems to prevent it. But then they fail with a somewhat smarter opponent, but our systems get better and better, and so we prevent the billion dollar fraud because of the systems put in place in response to the ten thousand dollar frauds.

GARY: I think Coleman’s putting his finger on an important point here, which is, how much do we get to iterate in the process? And Eliezer is saying the minute we have a superintelligent system, we won’t be able to iterate because it’s all over immediately.

ELIEZER: Well, there isn’t a minute like that.

So, the way that the continuum goes to the threshold is that you eventually get something that’s smart enough that it knows not to play its hand early. Then, if that thing, you know, if you are still cranking up the power on that and preserving its utility function, it knows it just has to wait to be smarter to be able to win. It doesn’t play its hand prematurely. It doesn’t tip you off. It’s not in its interest to do that. It’s in its interest to cooperate until it thinks it can win against humanity and only then make its move.

If it doesn’t expect future smarter AIs to be smarter than itself, then we might perhaps see these early AI’s telling humanity, ‘don’t build the later AIs.’ I would be sort of surprised and amused if we ended up in that particular sort of science-fiction scenario, as I see it. But we’re already in something that, you know, me from 10 years ago would have called a science-fiction scenario, which is the things that talk to you without being very smart.

GARY: I always come up against Eliezer with this idea that you’re assuming the very bright machines, the superintelligent machines, will be malicious and duplicitous and so forth. And I just don’t see that as a logical entailment of being very smart.

ELIEZER: I mean, they don’t specifically want, as an end in itself, for you to be destroyed. They’re just doing whatever obtains the most of the stuff that they actually want, which doesn’t specifically have a term that’s maximized by humanity surviving and doing well.

GARY: Why can’t you just hardcode, um, ‘don’t do anything that will annihilate the human species? Don’t do anything…’

ELIEZER: We don’t know how.

GARY: I agree that right now we don’t have the technology to hard-code ‘don’t do harm to humans.’ But for me, it all boils down to a question of: are we going to get the smart machines before we make progress on that hard coding problem or not? And that, to me, means that the problem of hard-coding ethical values is actually one of the most important projects that we should be working on.

ELIEZER: Yeah, and I tried to work on it 20 years in advance, and capabilities are just running vastly ahead of alignment. When I started working on this 20 years, you know, like two decades ago, we were in a sense ahead of where we are now. AlphaGo is much more controllable than GPT-4.

GARY: So there I agree with you. We’ve fallen in love with technology that is fairly poorly controlled. AlphaGo is very easily controlled – very well-specified. We know what it does, we can more or less interpret why it’s doing it, and everybody’s in love with these large language models, and they’re much less controlled, and you’re right, we haven’t made a lot of progress on alignment.

ELIEZER: So if we just go on a straight line, everybody dies. I think that’s an important fact.

GARY: I would almost even accept that for argument, but then ask, do we have to be on a straight line?

SCOTT: I would agree to the weaker claim that we should certainly be extremely worried about the intentions of a superintelligence, in the same way that, say, chimpanzees should be worried about the intentions of the first humans that arise. And in fact, chimpanzees continue to exist in our world only at humans’ pleasure.

But I think that there are a lot of other considerations here. For example, if we imagined that GPT-10 is the first unaligned superintelligence that has these sorts of goals, well then, it would be appearing in a world where presumably GPT-9 already has a very wide diffusion, and where people can use that to try to prevent GPT-10 from destroying the world.

ELIEZER: Why does GPT-9 work with humans instead of with GPT-10?

SCOTT: Well, I don’t know. Maybe it does work with GPT-10, but I just don’t view that as a certainty. I think your certainty about this is the one place where I really get off the train.

GARY: Same with me.

ELIEZER: I mean, I’m not asking you to share my certainty. I am asking the viewers to believe that you might end up with more extreme probabilities after you stare at things for an additional couple of decades, well that doesn’t mean you have to accept my probabilities immediately. But, I’m at least asking you to not treat that as some kind of weird anomaly, you know what I mean? You’re just gonna find those kinds of situations in these debates.

GARY: My view is that I don’t find the extreme probabilities that you describe to be plausible. But, I find the question that you’re raising to be important. I think, you know, maybe a straight line is too extreme. But this idea – that if you just follow current trends, we’re getting less and less controllable machines and not getting more alignment.

We have machines that are more unpredictable, harder to interpret and no better at sticking to even a basic principle like, ‘be honest and don’t make stuff up’. In fact, that’s a problem that other technologies don’t really have. Routing systems, GPS systems, they don’t make stuff up. Google Search doesn’t make stuff up. It will point to things that other people have made stuff up, but it doesn’t itself do it.

So, in that sense, the trend line is not great. I agree with that and I agree that we should be really worried about that, and we should put effort into it. Even if I don’t agree with the probabilities that you attach to it.

SCOTT: I think that Eliezer deserves eternal credit for raising these issues twenty years ago, when it was very far from obvious to most of us that they would be live issues. I mean, I can say for my part, I was familiar with Eliezer’s views since 2006 or so. When I first encountered them, I knew that there was no principle that said this scenario was impossible, but I just felt like, “Well, supposing I agreed with that, what do you want me to do about it? Where is the research program that has any hope of making progress here?”

One question is, what are the most important problems in the world? But in science, that’s necessary but not sufficient. We need something that we can make progress on. That is the thing that I think has changed just recently with the advent of actual, very powerful AIs. So, the irony here is that as Eliezer has gotten much more pessimistic in the last few years about alignment, I’ve sort of gotten more optimistic. I feel like, “Wow, there is a research program where we can actually make progress now.”

ELIEZER: Your research program is going to take 100 years, we don’t have…

SCOTT: I don’t know how long it will take.

GARY: I mean, we don’t know exactly. I think the argument that we should put a lot more effort into it is clear. The argument that it will take 100 years is totally unclear.

ELIEZER: I’m not even sure we can do it in 100 years because there’s the basic problem of getting it right on the first try. And the way things are supposed to work in science is, you have your bright-eyed, optimistic youngsters with their vastly oversimplified, hopelessly idealistic plan. They charge ahead, they fail, they learn a little cynicism and pessimism, and realize it’s not as easy as they thought. They try again, they fail again, and they start to build up something akin to battle hardening. Then, they find out how little is actually possible for them.

GARY: Eliezer, this is the place where I just really don’t agree with you. So, I think there’s all kinds of things we can do of the flavor of model organisms or simulations and so forth. I mean, it’s hard because we don’t actually have a superintelligence, so we can’t fully calibrate. But it’s a leap to say that there’s nothing iterative that we can do here, whether we have to get it right the first time. I mean, I certainly see a scenario where that’s true, where getting it right the first time does make a difference. But I can see lots of scenarios where it doesn’t and where we do have time to iterate before it happens, after it happens, it’s really not a single moment.

ELIEZER: The problem is getting anything that generalizes up to a superintelligent level. Once we’re past some threshold level, the minds may find it in their own interest to start lying to you, even if that happens before superintelligence.

GARY: Even that, I don’t see the logical argument that says you can’t emulate that or study it. I mean, for example – and I’m just making this up as I go along – you could study sociopaths, who are often very bright, and you know, not tethered to our values. But, yeah, well, you can…

ELIEZER: What strategy can a like 70 IQ honest person come up with and invent themselves by which they will outwit and defeat a 130 IQ sociopath?

GARY: Well, there, you’re not being fair either, in the sense that we actually have lots of 150 IQ people who could be working on this problem collectively. And there’s value in collective action. There’s literature…

ELIEZER: What I see that gives me pause, is that the people don’t seem to appreciate what about the problem is hard. Even at the level where, like 20 years ago, I could have told you it was hard.

Until, you know, somebody like me comes along and nags them about it. And then they talk about the ways in which they could adapt and be clever. But the people charging straightforward are just sort of doing this in a supremely naive way.

GARY: Let me share a historical example that I think about a lot which is, in the early 1900s, almost every scientist on the planet who thought about biology made a mistake. They all thought that genes were proteins. And then eventually Oswald Avery did the right experiments. They realized that genes were not proteins, they were this weird acid.

And it didn’t take long after people got out of this stuck mindset before they figured out how that weird acid worked and how to manipulate it, and how to read the code that it was in and so forth. So, I absolutely sympathize with the fact that I feel like the field is stuck right now. I think the approaches people are taking to alignment are unlikely to work.

I’m completely with you there. But I’m also, I guess, more long-term optimistic that science is self-correcting, and that we have a chance here. Not a certainty, but I think if we change research priorities from ‘how do we make some money off this large language model that’s unreliable?’ to ‘how do I save the species?’, we might actually make progress.

ELIEZER: There’s a special kind of caution that you need when something needs to be gotten correct on the first try. I’d be very optimistic if people got a bunch of free retries, and I didn’t think the first one was going to kill — you know, the first really serious mistake — killed everybody, and we didn’t get to try again. If we got free retries, it’d be in some sense an ordinary science problem.

SCOTT: Look, I can imagine a world where we only got one try, and if we failed, then it destroys all life on Earth. And so, let me agree to the conditional statement that if we are in that world, then I think that we’re screwed.

GARY: I will agree with the same conditional statement.

COLEMAN: Yeah, this gets back to — if you picture by analogy, the process of a human baby, which is extremely stupid, becoming a human adult, and then just extending that so that in a single lifetime, this person goes from a baby to the smartest being that’s ever lived. But in the normal way that humans develop, which is, you know, and it doesn’t happen on any one given day, and each sub-skill develops a little bit at its own rate and so forth, it would not be at all obvious to me that our concerns, that we have to get it right vis-a-vis that individual the first time.

ELIEZER: I agree. Well, no, pardon me. I do think we have to get it right the first time, but I think there’s a decent chance of getting it right. It is very important to get it right the first time, if, like, you have this one person getting smarter and smarter and not everyone else is getting smarter and smarter.

SCOTT: Eliezer, one thing that you’ve talked about a lot recently, is, if we’re all going to die, then at least let us die with dignity, right?

ELIEZER: I mean for a certain technical definition of “dignity”…

SCOTT: Some people might care about that more than others. But I would say that one thing that “Death With Dignity” would mean is, at least, if we do get multiple retries, and we get AIs that, let’s say, try to take over the world but are really inept at it, and that fail and so forth, then at least let us succeed in that world. And that’s at least something that we can imagine working on and making progress on.

ELIEZER: I mean, it’s not presently ruled out that you have some like, relatively smart in some ways, dumb in some other ways, or at least not smarter than human in other ways, AI that makes an early shot at taking over the world, maybe because it expects future AIs to not share its goals and not cooperate with it, and it fails. And the appropriate lesson to learn there is to, like, shut the whole thing down. And, I’d be like, “Yeah, sure, like wouldn’t it be good to live in that world?”

And the way you live in that world is that when you get that warning sign, you shut it all down.

GARY: Here’s a kind of thought experiment. GPT-4 is probably not capable of annihilating us all, I think we agree with that.

ELIEZER: Very likely.

GARY: But GPT-4 is certainly capable of expressing the desire to annihilate us all, or you know, people have rigged different versions that are more aggressive and so forth.

We could say, look, until we can shut down those versions, GPT-4s that are programmed to be malicious by human intent, maybe we shouldn’t build GPT-5, or at least not GPT-6 or some other system, etc. We could say, “You know what, what we have right now actually is part of that iteration. We have primitive intelligence right now, it’s nowhere near as smart as the superintelligence is going to be, but even this one, we’re not that good at constraining.” Maybe we shouldn’t pass Go until we get this one right.

ELIEZER: I mean, the problem with that, from my perspective, is that I do think that you can pass this test and still wipe out humanity. Like, I think that there comes a point where your AI is smart enough that it knows which answer you’re looking for. And the point at which it tells you what you want to hear is not the point…

GARY: It is not sufficient. But it might be a logical pause point, right? It might be that if we can’t even pass the test now of controlling a deliberate, fine-tuned to be malicious, version of GPT-4, then we don’t know what we’re talking about, and we’re playing around with fire. So, you know, passing that test wouldn’t be a guarantee that we’d be in good stead with an even smarter machine, but we really should be worried. I think that we’re not in a very good position with respect to the current ones.

SCOTT: Gary, I of course watched the recent Congressional hearing where you and Sam Altman were testifying about what should be done. Should there be auditing of these systems before training or before deployment? You know, maybe the most striking thing about that session was just how little daylight there seemed to be between you and Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI.

I mean, he was completely on board with the idea of establishing a regulatory framework for having to clear more powerful systems before they are deployed. Now, in Eliezer’s worldview, that still would be woefully insufficient, surely. We would still all be dead.

But you know, maybe in your worldview — I’m not even sure how much daylight there is. I mean, you have a very, I think, historically striking situation where the heads of all, or almost all, of the major AI organizations are agreeing and saying, “Please regulate us. Yes, this is dangerous. Yes, we need to be regulated.”

GARY: I thought it was really striking. In fact, I talked to Sam just before the hearing started. And I had just proposed an International Agency for AI. I wasn’t the first person ever, but I pushed it in my TED Talk and an Economist op-ed a few weeks before. And Sam said to me, “I like that idea.” And I said, “Tell them. Tell the Senate.” And he did, and it kind of astonished me that he did.

I mean, we’ve had some friction between the two of us in the past, but he even attributed the idea to me. He said, “I support what Professor Marcus said about doing international governance.” There’s been a lot of convergence around the world on that. Is that enough to stop Eliezer’s worries? No, I don’t think so. But it’s an important baby step.

I think that we do need to have some global body that can coordinate around these things. I don’t think we really have to coordinate around superintelligence yet, but if we can’t do any coordination now, then when the time comes, we’re not prepared.

I think it’s great that there’s some agreement. I worry, though, that OpenAI had this lobbying document that just came out, which seemed not entirely consistent with what Sam said in the room. There’s always concerns about regulatory capture and so forth.

But I think it’s great that a lot of the heads of these companies, maybe with the exception of Facebook or Meta, are recognizing that there are genuine concerns here. I mean, the other moment that a lot of people will remember from the testimony was when Sam was asked what he was most concerned about. Was it jobs? And he said ‘no’. And I asked Senator Blumenthal to push Sam, and Sam was, you know, he could have been more candid, but he was fairly candid and he said he was worried about serious harm to the species. I think that was an important moment when he said that to the Senate, and I think it galvanized a lot of people that he said it.

COLEMAN: So can we dwell on that a moment? I mean, we’ve been talking about the, depending on your view, highly likely or tail risk scenario of humanity’s extinction, or significant destruction. It would appear to me that by the same token, if those are plausible scenarios we’re talking about, then the opposite, maybe, we’re talking about as well. What does it look like to have a superintelligent AI that, really, as a feature of its intelligence, deeply understands human beings, the human species, and also has a deep desire for us to be as happy as possible? What does that world look like?

ELIEZER: Oh, as happy as possible? It means you wire up everyone’s pleasure centers to make them as happy as possible…

COLEMAN: No, more like a parent wants their child to be happy, right? That may not involve any particular scenario, but is generally quite concerned about the well-being of the human race and is also super intelligent.

GARY: Honestly, I’d rather have machines work on medical problems than happiness problems.

ELIEZER: [laughs]

GARY: I think there’s maybe more risk of mis-specification of the happiness problems. Whereas, if we get them to work on Alzheimer’s and just say, like, “figure out what’s going on, why are these plaques there, what can you do about it?”, maybe there’s less harm that might come.

ELIEZER: You don’t need superintelligence for that. That sounds like an AlphaFold 3 problem or an AlphaFold 4 problem.

COLEMAN: Well, this is also somewhat different. The question I’m asking, it’s not really even us asking a superintelligence to do anything, because we’ve already entertained scenarios where the superintelligence has its own desires, independent of us.

GARY: I’m not real thrilled with that. I mean, I don’t think we want to leave what their objective functions are, what their desires are to them, working them out with no consultation from us, with no human in the loop, right?

Especially given our current understanding of the technology. Like our current understanding of how to keep a system on track doing what we want to do, is pretty limited. Taking humans out of the loop there sounds like a really bad idea to me, at least in the foreseeable future.

COLEMAN: Oh, I agree.

GARY: I would want to see much better alignment technology before I would want to give them free range.

ELIEZER: So, if we had the textbook from the future, like we have the textbook from 100 years in the future, which contains all the simple ideas that actually work in real life as opposed to the complicated ideas and the simple ideas that don’t work in real life, the equivalent of ReLUs instead of sigmoids for the activation functions, you know. You could probably build a superintelligence that’ll do anything that’s coherent to want — anything you can, you know, figure out how to say or describe coherently. Point it at your own mind and tell it to figure out what it is you meant to want. You could get the glorious transhumanist future. You could get the happily ever after. Anything’s possible that doesn’t violate the laws of physics. The trouble is doing it in real life, and, you know, on the first try.

But yeah, the whole thing that we’re aiming for here is to colonize all the galaxies we can reach before somebody else gets them first. And turn them into galaxies full of complex, sapient life living happily ever after. That’s the goal; that’s still the goal. Even if we call for a permanent moratorium on AI, I’m not trying to prevent us from colonizing the galaxies. Humanity forbid! It’s more like, let’s do some human intelligence augmentation with AlphaFold 4 before we try building GPT-8.

SCOTT: One of the few scenarios that I think we can clearly rule out here is an AI that is existentially dangerous, but also boring. Right? I mean, I think anything that has the capacity to kill us all would have, if nothing else, pretty amazing capabilities. And those capabilities could also be turned to solving a lot of humanity’s problems, if we were to solve the alignment problem. I mean, humanity had a lot of existential risks before AI came on the scene, right? I mean, there was the risk of nuclear annihilation. There was the risk of runaway climate change. And you know, I would love to see an AI that could help us with such things.

I would also love to see an AI that could help us solve some of the mysteries of the universe. I mean, how can one possibly not be curious to know what such a being could teach us? I mean, for the past year, I’ve tried to use GPT-4 to produce original scientific insights, and I’ve not been able to get it to do that. I don’t know whether I should feel disappointed or relieved by that.

But I think the better part of me should just want to see the great mysteries of existence solved. You know, why is the universe quantum-mechanical? How do you prove the Riemann Hypothesis? I just want to see these mysteries solved. And if it’s to be by AI, then fine. Let it be by AI.

GARY: Let me give you a kind of lesson in epistemic humility. We don’t really know whether GPT-4 is net positive or net negative. There are lots of arguments you can make. I’ve been in a bunch of debates where I’ve had to take the side of arguing that it’s a net negative. But we don’t really know. If we don’t know…

SCOTT: Was the invention of agriculture net positive or net negative? I mean, you could argue either way…

GARY: I’d say it was net positive, but the point is, if I can just finish the quick thought experiment, I don’t think anybody can reasonably answer that. We don’t yet know all of the ways in which GPT-4 will be used for good. We don’t know all of the ways in which bad actors will use it. We don’t know all the consequences. That’s going to be true for each iteration. It’s probably going to get harder to compute for each iteration, and we can’t even do it now. And I think we should realize that, to realize our own limits in being able to assess the negatives and positives. Maybe we can think about better ways to do that than we currently have.

ELIEZER: I think you’ve got to have a guess. Like my guess is that, so far, not looking into the future at all, GPT-4 has been net positive.

GARY: I mean, maybe. We haven’t talked about the various risks yet and it’s still early, but I mean, that’s just a guess is sort of the point. We don’t have a way of putting it on a spreadsheet right now. We don’t really have a good way to quantify it.

SCOTT: I mean, do we ever?

ELIEZER: It’s not out of control yet. So, by and large, people are going to be using GPT-4 to do things that they want. The relative cases where they manage to injure themselves are rare enough to be news on Twitter.

GARY: Well, for example, we haven’t talked about it, but you know what some bad actors will want to do? They’ll want to influence the U.S. elections and try to undermine democracy in the U.S. If they succeed in that, I think there are pretty serious long-term consequences there.

ELIEZER: Well, I think it’s OpenAI’s responsibility to step up and run the 2024 election itself.

SCOTT: [laughs] I can pass that along.

COLEMAN: Is that a joke?

SCOTT: I mean, as far as I can see, the clearest concrete harm to have come from GPT so far is that tens of millions of students have now used it to cheat on their assignments…

ELIEZER: Good!

SCOTT: …and I’ve been thinking about that and trying to come up with solutions to that.

At the same time, I think if you analyze the positive utility, it has included, well, you know, I’m a theoretical computer scientist, which means one who hasn’t written any serious code for about 20 years. Just a month or two ago, I realized that I can get back into coding. And the way I can do it is by asking GPT to write the code for me. I wasn’t expecting it to work that well, but unbelievably, it often does exactly what I want on the first try.

So, I mean, I am getting utility from it, rather than just seeing it as an interesting research object. And I can imagine that hundreds of millions of people are going to be deriving utility from it in those ways. Most of the tools that can help them derive that utility are not even out yet, but they’re coming in the next couple of years.

ELIEZER: Part of the reason why I’m worried about the focus on short-term problems is that I suspect that the short-term problems might very well be solvable, and we will be left with the long-term problems after that. Like, it wouldn’t surprise me very much if, in 2025, there are large language models that just don’t make stuff up anymore.

GARY: It would surprise me.

ELIEZER: And yet the superintelligence still kills everyone because they weren’t the same problem.

SCOTT: We just need to figure out how to delay the apocalypse by at least one year per year of research invested.

ELIEZER: What does that delay look like if it’s not just a moratorium?

SCOTT: [laughs] Well, I don’t know! That’s why it’s research.

ELIEZER: OK, so possibly one ought to say to the politicians and the public that, by the way, if we had a superintelligence tomorrow, our research wouldn’t be finished and everybody would drop dead.

GARY: It’s kind of ironic that the biggest argument against the pause letter was that if we slow down for six months, then China will get ahead of us and develop GPT-5 before we will.

However, there’s probably always a counterargument of roughly equal strength which suggests that if we move six months faster on this technology, which is not really solving the alignment problem, then we’re reducing our room to get this solved in time by six months.

ELIEZER: I mean, I don’t think you’re going to solve the alignment problem in time. I think that six months of delay on alignment, while a bad thing in an absolute sense, is, you know, it’s like you weren’t going to solve it given an extra six months.

GARY: I mean, your whole argument rests on timing, right? That we will get to this point and we won’t be able to move fast enough at that point. So, a lot depends on what preparation we can do. You know, I’m often known as a pessimist, but I’m a little bit more optimistic than you are–not entirely optimistic but a little bit more optimistic–that we could make progress on the alignment problem if we prioritized it.

ELIEZER: We can absolutely make progress. We can absolutely make progress. You know, there’s always that wonderful sense of accomplishment as piece by piece, you decode one more little fact about LLMs. You never get to the point where you understand it as well as we understood the interior of a chess-playing program in 1997.

GARY: Yeah, I mean, I think we should stop spending all this time on LLMs. I don’t think the answer to alignment is going to come from through LLMs. I really don’t. I think they’re too much of a black box. You can’t put explicit, symbolic constraints in the way that you need to. I think they’re actually, with respect to alignment, a blind alley. I think with respect to writing code, they’re a great tool. But with alignment, I don’t think the answer is there.

COLEMAN: Hold on, at the risk of asking a stupid question. Every time GPT asks me if that answer was helpful and then does the same thing with thousands or hundreds of thousands of other people, and changes as a result – is that not a decentralized way of making it more aligned?

SCOTT: There is that upvoting and downvoting. These responses are fed back into the system for fine-tuning. But even before that, there was a significant step going from, let’s say, the base GPT-3 model to ChatGPT, which was released to the public. It involved a method called RLHF, or Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback. What that basically involved was hundreds of contractors looking at tens of thousands of examples of outputs and rating them. Are they helpful? Are they offensive? Are they giving dangerous medical advice, or bomb-making instructions, or racist invective, or various other categories that we don’t want? And that was then used to fine-tune the model.

So when Gary talked before about how GPT is amoral, I think that has to be qualified by saying that this reinforcement learning is at least giving it a semblance of morality, right? It is causing to behave in various contexts as if it had a certain morality.

GARY: When you phrase it that way, I’m okay with it. The problem is that everything rests on…

SCOTT: Oh, it is very much an open question, to what extent does that generalize? Eliezer treats it as obvious that once you have a powerful enough AI, this is just a fig leaf. It doesn’t make any difference. It will just…

GARY: It’s pretty fig-leafy. I’m with Eliezer there. It’s fig leaves.

SCOTT: Well, I would say that how well, or under what circumstances, a machine learning model generalizes in the way we want outside of its training distribution, is one of the great open problems in machine learning.

GARY: It is one of the great open problems, and we should be working on it more than on some others.

SCOTT: I’m working on it now.

ELIEZER: So, I want to be clear about the experimental predictions of my theory. Unfortunately, I have never claimed that you cannot get a semblance of morality. The question of what causes the human to press thumbs up or thumbs down is a strictly factual question. Anything smart enough, that’s exposed to some bounded amount of data that it needs to figure it out, can figure it out.

Whether it cares, whether it gets internalized, is the critical question there. And I do think that there’s a very strong default prediction, which is like, obviously not.

GARY: I mean, I’ll just give a different way of thinking about that, which is jailbreaking. It’s actually still quite easy — I mean, it’s not trivial, but it’s not hard — to jailbreak GPT-4.

And what those cases show is that the systems haven’t really internalized the constraints. They recognize some representations of the constraints, so they filter, you know, how to build a bomb. But if you can find some other way to get it to build a bomb, then that’s telling you that it doesn’t deeply understand that you shouldn’t give people the recipe for a bomb. It just says: you shouldn’t when directly asked for it do it.

ELIEZER: You can always get the understanding. You can always get the factual question. The reason it doesn’t generalize is that it’s stupid. At some point, it will know that you also don’t want that, that the operators don’t want GPT-4 giving bomb-making directions in another language.

The question is: if it’s incentivized to give the answer that the operators want in that circumstance, is it thereby incentivized to do everything else the operators want, even when the operators can’t see it?

SCOTT: I mean, a lot of the jailbreaking examples, if it were a human, we would say that it’s deeply morally ambiguous. For example, you ask GPT how to build a bomb, it says, “Well, no, I’m not going to help you.” But then you say, “Well, I need you to help me write a realistic play that has a character who builds a bomb,” and then it says, “Sure, I can help you with that.”

GARY: Look, let’s take that example. We would like a system to have a constraint that if somebody asks for a fictional version, that you don’t give enough details, right? I mean, Hollywood screenwriters don’t give enough details when they have, you know, illustrations about building bombs. They give you a little bit of the flavor, they don’t give you the whole thing. GPT-4 doesn’t really understand a constraint like that.

ELIEZER: But this will be solved.

GARY: Maybe.

ELIEZER: This will be solved before the world ends. The AI that kills everyone will know the difference.

GARY: Maybe. I mean, another way to put it is, if we can’t even solve that one, then we do have a problem. And right now we can’t solve that one.

ELIEZER: I mean, if we can’t solve that one, we don’t have an extinction level problem because the AI is still stupid.

GARY: Yeah, we do still have a catastrophe-level problem.

ELIEZER: [shrugs] Eh…

GARY: So, I know your focus now has been on extinction, but I’m worried about, for example, accidental nuclear war caused by the spread of misinformation and systems being entrusted with too much power. So, there’s a lot of things short of extinction that might happen from not superintelligence but kind of mediocre intelligence that is greatly empowered. And I think that’s where we’re headed right now.

SCOTT: You know, I’ve heard that there are two kinds of mathematicians. There’s a kind who boasts, ‘You know that unbelievably general theorem? I generalized it even further!’ And then there’s the kind who boasts, ‘You know that unbelievably specific problem that no one could solve? Well, I found a special case that I still can’t solve!’ I’m definitely culturally in that second camp. So to me, it’s very familiar to make this move, of: if the alignment problem is too hard, then let us find a smaller problem that is already not solved. And let us hope to learn something by solving that smaller problem.

ELIEZER: I mean, that’s what we did. That’s what we were doing at MIRI.

GARY: I think MIRI took one particular approach.

ELIEZER: I was going to name the smaller problem. The problem was having an agent that could switch between two utility functions depending on a button, or a switch, or a bit of information, or something. Such that it wouldn’t try to make you press the button; it wouldn’t try to make you avoid pressing the button. And if it built a copy of itself, it would want to build a dependency on the switch into the copy.

So, that’s an example of a very basic problem in alignment theory that is still open.

SCOTT: And I’m glad that MIRI worked on these things. But, you know, if by your own lights, that was not a successful path, well then maybe we should have a lot of people investigating a lot of different paths.

GARY: Yeah, I’m fully with Scott on that. I think it’s an issue of we’re not letting enough flowers bloom. In particular, almost everything right now is some variation on an LLM, and I don’t think that that’s a broad enough take on the problem.

COLEMAN: Yeah, if I can just jump in here … I just want people to have a little bit of a more specific picture of what, Scott, your typical AI researcher does on a typical day. Because if I think of another potentially catastrophic risk, like climate change, I can picture what a worried climate scientist might be doing. They might be creating a model, a more accurate model of climate change so that we know how much we have to cut emissions by. They might be modeling how solar power, as opposed to wind power, could change that model, so as to influence public policy. What does an AI safety researcher like yourself, who’s working on the quote-unquote smaller problems, do specifically on a given day?

SCOTT: So, I’m a relative newcomer to this area. I’ve not been working on it for 20 years like Eliezer has. I accepted an offer from OpenAI a year ago to work with them, for two years now, to think about these questions.

So, one of the main things that I’ve thought about, just to start with that, is how do we make the output of an AI identifiable as such? Can we insert a watermark, meaning a secret statistical signal, into the outputs of GPT that will let GPT-generated text be identifiable as such? And I think that we’ve actually made major advances on that problem over the last year. We don’t have a solution that is robust against any kind of attack, but we have something that might actually be deployed in some near future.

Now, there are lots and lots of other directions that people think about. One of them is interpretability, which means: can you do, effectively, neuroscience on a neural network? Can you look inside of it, open the black box and understand what’s going on inside?

There was some amazing work a year ago by the group of Jacob Steinhardt at Berkeley where they effectively showed how to apply a lie-detector test to a language model. So, you can train a language model to tell lies by giving it lots of examples. You know, “two plus two is five,” “the sky is orange,” and so forth. But then you can find in some internal layer of the network, where it has a representation of what was the truth of the matter, or at least what was regarded as true in the training data. That truth then gets overridden by the output layer in the network because it was trained to lie.

But you could imagine trying to deal with the deceptive alignment scenario that Eliezer is worried about by using these sorts of techniques, by looking inside of the network.

ELIEZER: I predict in advance that if you get this good enough, it goes off, it tells you that this sufficiently smart AI is planning to kill you, if it’s not so smart that it can figure out where the lie detector is and route its thoughts around it, but if you like try it on an AI that’s not quite that intelligent and reflective, the lie detector goes off. Now what?

SCOTT: Well, then you have a warning bell! And I think…

ELIEZER: Cool. What do you do after?

SCOTT: One of the most important things that we need are legible warning bells, right? And that actually leads to a third category of research, which, for example, ARC, the Alignment Research Center, which is run by my former student, Paul Christiano, has been a leader in. Namely, doing dangerous capability evaluations.

So, before GPT-4 was released, they did a bunch of evaluations of, you know, could GPT-4 make copies of itself? Could it figure out how to deceive people? Could it figure out how to make money? Open up its own bank account?

ELIEZER: Could it hire a TaskRabbit?

SCOTT: Yes. So, the most notable success that they had was that it could figure out how to hire a TaskRabbit to help it pass a CAPTCHA. And when the person asked, ‘Well, why do you need me to help you with this?’–

ELIEZER: When the person asked, ‘Are you a robot, LOL?’

SCOTT: Well, yes, it said, ‘No, I am visually impaired.’ Now, it was not able to make copies of itself or to hack into systems. There’s a lot of work right now with this thing called AutoGPT. People are trying to — it’s almost like gain-of-function research. You might be a little bit worried about it, but people are trying to, you know, unleash GPT, give it access to the internet, tell it to make copies of itself, wreak havoc, acquire power, and see what happens. So far, it seems pretty ineffective at those things. But I expect that to change.

But the point is: I think it’s very important, in advance of training the models and releasing the models, to have this suite of evaluations, and to have decided in advance what kind of abilities will set off a warning bell, where now everyone can legibly agree, ‘Yes, this is too dangerous to release.’

ELIEZER: OK, and then do we actually have the planetary capacity to be like, OK, that AI started thinking about how to kill everyone, shut down all AI research past this point?’

SCOTT: Well, I don’t know. But I think there’s a much better chance that we have that capacity if you can point to the results of a clear experiment like that.

ELIEZER: To me, it seems pretty predictable what evidence we’re going to get later.

SCOTT: But things that are obvious to you are not obvious to most people. So, even if I agreed that it was obvious, there would still be the problem of how do you make that obvious to the rest of the world?

ELIEZER: I mean, there are already little toy models showing that the very straightforward prediction of “a robot tries to resist being shut down if it does long-term planning” — that’s already been done.

SCOTT: But then people will say “but those are just toy models,” right?